Summary

Food insecurity is a significant issue among U.S. college students, including those at Georgia Tech, where 26% of surveyed (55) students reported food insecurity. Research highlights that stigma and accessibility challenges often prevent students from seeking help, while inconsistent resource availability adds to the difficulty. Our project aimed to address these barriers by creating a solution that reduces stigma, increases awareness, and improves access to food resources on campus by leveraging existing infrastructure around Klemis Kitchen (campus food pantry) and visiting food trucks.

Role: Team Lead, Design and Branding Lead, Research & Prototyping

Problem Space

Addressing Student Food Insecurity with Klemis Commons

Background Research

Food insecurity among college students is more prevalent than in the general population, with many students experiencing anxiety about where their next meal will come from. At Georgia Tech, 26% of surveyed students reported food insecurity. Barriers to seeking assistance include stigma and misconceptions that food resources are only for the most destitute. Coping mechanisms, such as relying on free campus events for meals or purchasing cheap, unhealthy food, highlight the need for accessible and dignified solutions.

Site Observations of Existing Systems

Existing systems for addressing food insecurity include resources like Klemis Kitchen, community fridges, and campus dining programs. Our team visited each system, taking time to volunteer at Klemis Kitchen and Atlanta Community Foodbank to capture 1st-hand experience in the upstream process for food resources.

High-Level System Analysis of Existing Systems

Klemis Kitchen provides pre-packaged meals and shelf-stable donations but suffers from limited awareness and occasional logistical challenges.

Community fridges offer anonymous, stigma-free access to food but lack digital promotion and consistent updates.

Campus dining programs, such as Tech Dining, provide meal benefits for student employees but are not widely accessible to all food-insecure students.

Atlanta Community Food Bank is well-organized but faces volunteer shortages due to its scale. Distance from campus makes access challenging for students, though delivery options are available on specific days.

Primary Research

Our research combined site observations (above), surveys, interviews, and empathy mapping to build a comprehensive understanding of food insecurity among Georgia Tech students. Each method provided targeted insights into the challenges students face, directly informing the system requirements for the design phase.

Summarized User Journey and Identified Characteristics

Characteristics of our Users

Increased Health Risks: Food-insecure students often experience physical and mental health challenges, including poor sleep and a reliance on unhealthy food due to cost constraints.

Stigma and Shame: Many students avoid seeking help due to embarrassment or fear of judgment, even when resources are available.

Resourcefulness: Students employ creative coping strategies, such as leveraging free campus meal events.

Resilience: Despite challenges, many food-insecure students demonstrate determination to succeed academically while balancing financial and personal hardships.

Design Requirements from Primary Research

Functional Requirements

Dietary Autonomy: Users should have control over their food choices based on personal dietary needs and preferences. Visibility into food options that fit dietary restrictions ensures confidence and satisfaction.

Facilitating Awareness: The system must provide clear and accessible information about available resources to increase awareness. This includes promoting awareness through digital platforms and physical signage.

Consistent Food Visibility: Ensure users can reliably access accurate information about available food options. Real-time updates and transparency about stock levels are critical.

Convenient Access: Resources should be easy to locate and integrate seamlessly into students’ daily routines. This includes digital tools for navigation and campus-wide physical accessibility.

Protecting Users’ Information: Maintain user privacy while accessing food resources to ensure dignity and build trust.

Non-Functional Requirements

Protect Dignity and Independence: Design systems that reduce stigma, allowing users to access resources discreetly and independently. Focus on creating a “normal” experience that doesn’t feel like a support program.

Cross-Culturally Informative: Ensure resources are inclusive and resonate with users from diverse cultural backgrounds. Onboarding should reflect an understanding of cultural nuances and varying perceptions of social services.

Ideation

We leveraged various ideation methods to increase our chances of landing on a creative, novel solution aligned to the above requirements. Each method was completed in a separate session and reviewed for relevance, strengths, and weaknesses.

Rapid Brainstorming and Ideas as Metaphors

Our general ideation process began with a 10-minute rapid ideation where we had 19 relevant concepts out of 61 total generated. Of those 19, 8 were expanded upon through an "ideation as metaphors" phase.

Brainwriting

To ensure alignment with our design requirements, we then did a session of brainwriting using the design requirements for structure and expanding upon the previously generated ideas while adding more to the mix as creativity flowed.

Springboarding

We dot-voted on the strongest concepts, grouped them by like-concepts, and then did a round of springboarding to create "I wish" and "How to" statements relating to the strongest concepts to capture potential opportunities based on our understood user perspective.

Concepts & Final Direction

Our concepts spanned a variety of idea-types, each meeting 2-3 design requirements from primary research. Through team discussions, feedback sessions with our TAs and professor, our strongest directions were chosen to storyboard and test for user feedback.

Final Direction: Food Truck Experience

Partnerships with campus food trucks to provide free or reduced-cost meals for food-insecure students. Meals are accessed via Buzzcard integration and designed to feel like a standard food truck interaction.

Strengths

This concept supports dietary autonomy by giving users control over their meal choices. By providing food-insecure students with protected meal funds, it also preserves their dignity, making the experience feel like a typical food truck visit. Lastly, it improves convenience by using existing Buzzcard infrastructure and centrally located food trucks.

Weaknesses

Implementing this solution would require complex negotiations with food truck vendors to determine funding—whether through Georgia Tech, the STAR program, or donations. Additionally, the rollout would involve a lengthy timeline due to the need for system integration and logistical planning.

Implementing this solution would require complex negotiations with food truck vendors to determine funding—whether through Georgia Tech, the STAR program, or donations. Additionally, the rollout would involve a lengthy timeline due to the need for system integration and logistical planning.

Branding & Visual Design

While we gathered concept feedback, we were tasked with creating the system design language aligned to the ethos of our users and the spirit of our solution.

Klemis Commons Brand

In our approach, we aimed to capture the ideas of warmth, diversity, and cultural inclusivity. We pulled inspiration from Klemis Kitchen’s branding, incorporating greens to create a strong connection to its mission. Our imagery also reflects the feel of outdoor markets, which are familiar and welcoming across different cultures globally, helping to reinforce the sense of community and support we wanted to convey.

Final Solution

Klemis Commons: A Holistic Solution for Food Insecurity at Georgia Tech

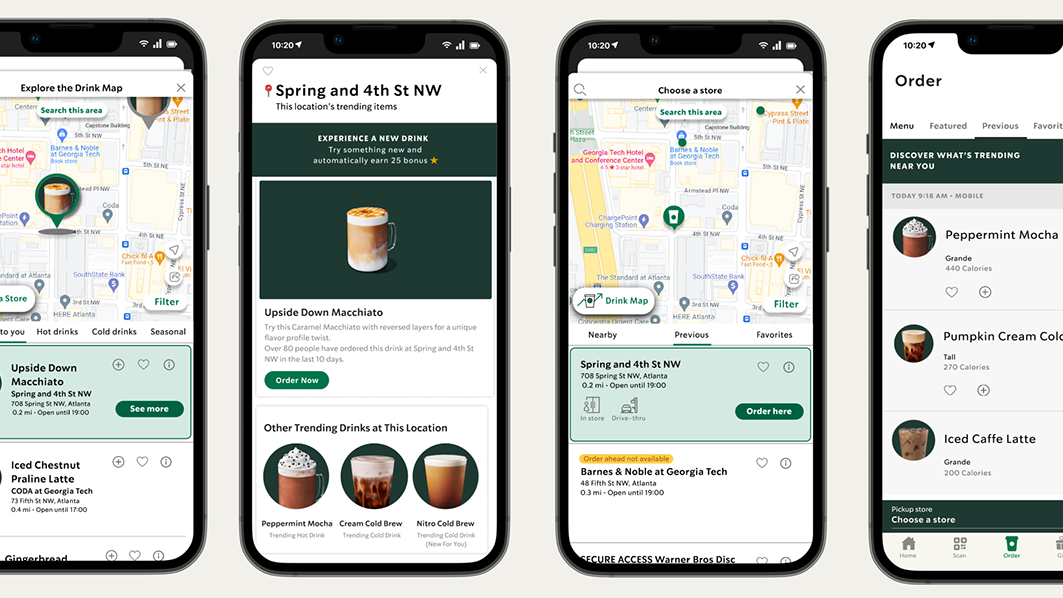

What started as the "Food Truck Experience" evolved into Klemis Commons—a centralized platform designed to address food insecurity by connecting Georgia Tech students to all available food resources. More than just an information hub, Klemis Commons empowers students with tools for managing and accessing food assistance, creating a seamless and dignified experience for those in need.

Built to grow with Georgia Tech’s evolving food resources, Klemis Commons leverages existing Buzzcard permissions for features like Klemis Cash, ensuring secure and efficient access for qualifying students. This platform is a scalable, student-centered solution that fosters dignity, convenience, and accessibility in tackling food insecurity on campus.

Key Features

Comprehensive Resource Hub: Up-to-date details about Klemis Kitchen, including hours, locations, and restock dates.

Klemis Cash: Redeemable funds for meals at campus food trucks, providing flexibility and dietary autonomy.

Community Garden Integration: Volunteer opportunities in exchange for fresh produce and seasonal crop information.

Event Calendar: A curated schedule of meal nights hosted by community organizations, tailored to dietary needs.

Streamlined Notifications: Alerts for food drop-offs and updates on resource availability.

Evaluation

General Process

We employed both Discount Evaluation and User-Testing methods to validate our solution and capture feedback for future work. Each method captured a different audience, and so, we wanted to test success of different design criteria based on those users and the expertise they would offer us.

Discount Evaluation

We did task-based scenario testing with 5 of our classmates to capture think-aloud feedback, SUS scores, and answers to Likert Scale questions. Our classmates were used to identify usability issues and validate functionality in a controlled environment. Their tasks tested for the "Convenient Access" and "Dietary Autonomy" design criteria by asking them to locate food trucks, donation drop-off information, and the success rate of accessing similar information across other Georgia Tech platforms.

User Testing

We also did task-based scenario testing with actual patrons of Klemis Kitchen. Their participation was rewarded with 30 dollars in buzzfunds sponsored by the director of the STAR program and his support in our efforts to design this concept. These funds were used to support a life-like simulation of accessing diet-specific food truck menus and locating qualifying information for Klemis Cash. These tasks tested the "Dignity and Independence" and "Cross Culturally Understandable" design requirements.

Analysis

Think-aloud feedback was affinity-mapped and grouped by key themes. Quantitative data from SUS and Likert questions were measured for usability and alignment of design goals.

Conclusions

Due to the limited time we had in the semester, we were only able to test for the 4 design criteria mentioned above, so our results and lessons learned are oriented around the information we were able to gather in our limited testing.

Outcomes and Future Work

Convenient Access: Users found food truck information intuitive, but schedule tiles needed more details for quick comparisons. This means that we should consider adding more descriptive icons and interaction cues to enhance usability.

Dietary Autonomy: Users appreciated dietary filters but struggled with unfamiliar dietary terms. In the future, we should define terms and refine filter categories to be more inclusive and user-friendly.

Protecting Dignity and Independence: Branding was warm and welcoming, but users hesitated to rely solely on Klemis Cash due to potential technical issues. In the future, we should consider adding instructions for handling payment failures to build trust and confidence.

Cross-Cultural Understandability: Onboarding and eligibility explanations were unclear, leaving users confused. For us, this means we should improve onboarding content to explain eligibility and relationships between system components.

Lessons Learned

Problem Definition

Early in the project, our problem statement was too broad, as we initially aimed to address both food and housing insecurity. Narrowing our focus to food insecurity allowed us to conduct deeper research and develop more impactful solutions.

Design Process

Starting the design phase earlier would have allowed more time for refinement and iteration. While paper prototyping provided valuable feedback, transitioning to higher-fidelity designs revealed areas that could have benefited from earlier ideation. Additionally, learning Figma during the project took time that could have been spent polishing interactions. Introducing participatory design earlier would have enriched our process, as designing with users could have provided more nuanced insights. Despite this, our enactment exercise, specifically having users test the prototype and visit a food truck, offered meaningful validation.

Ideation

Our ideation phase was fast-paced, and while the "Food Truck Experience" was initially the most novel concept, it evolved into a broader system: Klemis Commons. This clarified that the food trucks were just one component of a larger solution, and refined how we communicated the concept as a cohesive hub and system, rather than a single transactional solution.